Electrical emissions in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) increased last year, and the reasons behind it deserve more attention than they are getting.

Electricity-related emissions in the region jumped close to thirty per cent despite almost no change in demand. The trend is tied to Ontario’s growing dependence on natural gas due to nuclear refurbishments taking major generation units offline and rising local electricity demand that has been met almost entirely by gas-fired power.

The emissions-free share of Ontario’s electricity supply has been shrinking for years, falling from roughly 96 per cent to about 84 per cent (Ontario). That erosion matters. Even at 84 per cent, Ontario remains cleaner than many jurisdictions globally, but the direction of travel has reversed.

A new reality

Companies that have been basing their decarbonization confidence on an ever-cleaner grid are now facing a different reality.

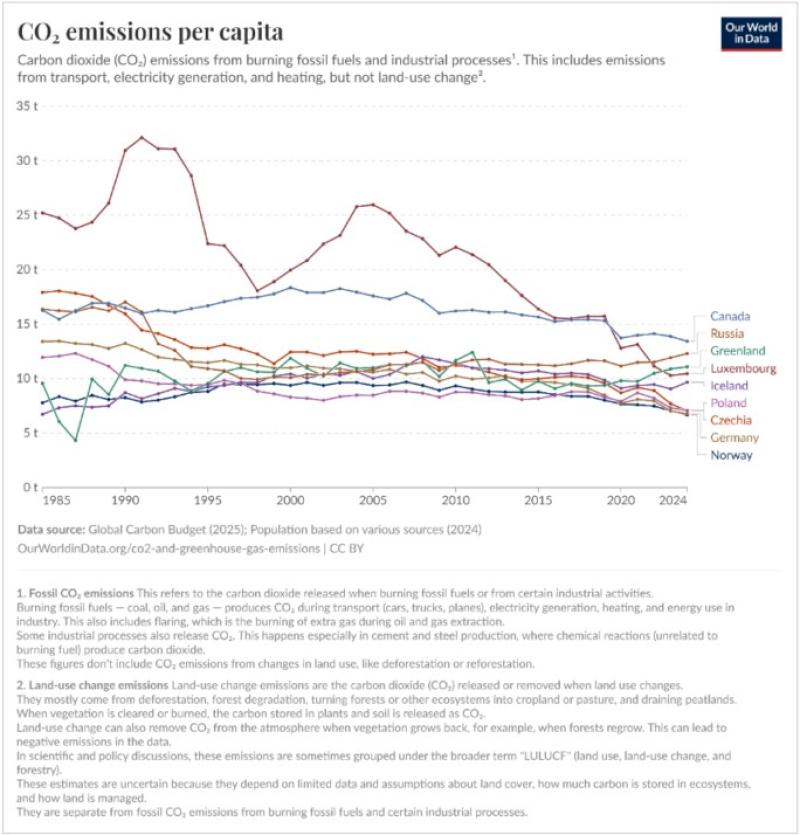

National numbers are no more encouraging. Canada has reduced emissions by roughly nine per cent since 2005, while other G7 countries have achieved reductions far beyond that.

The United Kingdom has cut close to half its emissions over the same period. Even the United States has moved faster. Canada still sits among the highest per-capita emitters in the world, and the gap between our peers and us keeps widening.

These issues are usually framed as policy failures or supply-side challenges, but the private sector has its own habit of waiting for external forces to make progress easier. Many organizations still assume their emissions profile will naturally improve as grids, technologies and regulations evolve.

The problem is that none of those shifts are moving at the pace that companies expect, and the GTHA numbers are a clear example of what happens when the underlying system starts moving in the opposite direction.

Carbon emission tracking and reporting is rapidly shifting from voluntary to mandatory. Jurisdictions worldwide are implementing carbon border adjustments and disclosure requirements.

California’s SB 253 and SB 261 are prime examples, requiring companies with over US$1 billion in revenue to publicly report Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions starting in 2026. Energy and carbon management cannot rely on passive optimism.

If a region’s grid becomes more carbon-intensive, a company’s emissions rise even when consumption stays the same. If building performance remains unchanged year after year, the long-term cost exposure keeps growing. If internal decision-making remains slow or reactive, the organization loses control of its own trajectory and must absorb whatever direction the market takes next.

How to avoid the trap

The companies that avoid this trap are the ones that treat energy data as something that needs continuous attention rather than annual review.

They track changes in their portfolio and local grid behaviour. They invest in operational improvements that reduce demand instead of hoping electricity supply will improve on its own. They move early on retrofits, load management, behavioural programs and long-term planning because they understand that delay only makes every option more expensive.

We have seen organizations achieve cost and emissions reductions of approximately five per cent per year when they commit to this kind of groundwork. Their advantage comes from consistency and structure, not from waiting for external momentum. They act first, measure properly and adjust often. Nothing about their progress depends on luck.

Canada’s current trajectory makes one point unavoidable. Businesses that want lower emissions cannot depend on regional or national performance to carry them forward. They need a strategy that works even when the broader system slows down, and they need tools that reveal problems early enough to act on them.

Companies that build that foundation now will avoid the volatility already visible in the GTHA numbers.

At 360 Energy, we work with companies who cut their energy bills and emissions because they track, analyze and act. No one is waiting for a perfect policy or a perfect year. Instead, they use current data to steer decisions, benchmark against peers, and make improvements that actually stick.

The grid is not getting cleaner on its own. The companies who win are those who stop waiting.